All this and love and mercy, too ...

A longtime fan goes long – like, real long – on the artist who created so much of the soundtrack of her life, Brian Wilson.

NOTE: I started this the day after Brian died. It was a combination of having lots more to say than I imagined, and, well, life getting in the way; hence, the longish delay. Meanwhile, if you want to listen to all or part of my June 19th Brian tribute on Cygnus Radio, have at it.

Oh, God, this was a tough one. The toughest.

I knew the clock was running on Brian Wilson. I mean, he was days away from 83 (his birthday would’ve been June 20) and he had dementia. But I still wasn’t ready.

I was pulling into the garage bay of my car dealer for some routine work about 10 after 1 June 11 when the DJ on the Sirius XM ’60s Gold channel said, “I have some sad news to pass along. It’s been confirmed; it’s official. Brian Wilson …”

I let out a loud groan and went numb, stunned, trying to process as I got out of the car and zombied my way into the waiting room. Imagine learning that someone who meant a lot to you has died and you have to keep your emotions in check for the next two hours. I didn’t have to imagine – that was my reality.

Just after 3, I pulled out of the dealer and headed toward home. Pat St. John had taken over the mic, the station had already quickly whipped up promos marking Brian’s passing, and he would occasionally give some recollection of Brian. And as I pulled away, I was floored by the song he played next: Brian and Al Jardine and a slew of singers and musicians backing them singing “My Sweet Lord.” It’s kinda difficult to drive with some foreign object blurring your vision.

Back in town and a couple minutes from home, I drove by my friend Sarah’s house and stopped and called her, not knowing whether she was working. She was kind enough to come outside. There was one person aside from family and close friends whom I knew would get me to the point of verklempt when they died, and that was Brian. That’s how much his music has meant to me. She was kind enough to give me a huge hug and a shoulder to let out this one ugly bit of emotion.

Anyway, I don’t think I can keep a straight narrative; my thoughts and memories are strewn like so many like so many bits and splices of his Pet Sounds and Smile sessions, only with less resonance. My words are fleeting; Brian’s music is forever.

*****

The setting: the lobby of Nassau Hall, my dorm at Long Island University’s C.W. Post campus, a winter Thursday-Friday overnight, late January 1980.

I was just hanging out there this late hour, as I was and still am a night owl, and I was talking to my hallmate and future frat brother Scott Bergmann, who was sitting desk.

“You’re a big fan of The Beach Boys,” he said. I had a few store-bought cassettes I would play on the radio/cassette player in my room, where I had also taped up the giant record store promo poster for the L.A. (Light Album). “I’ll let you borrow this book. I think you should read it.”

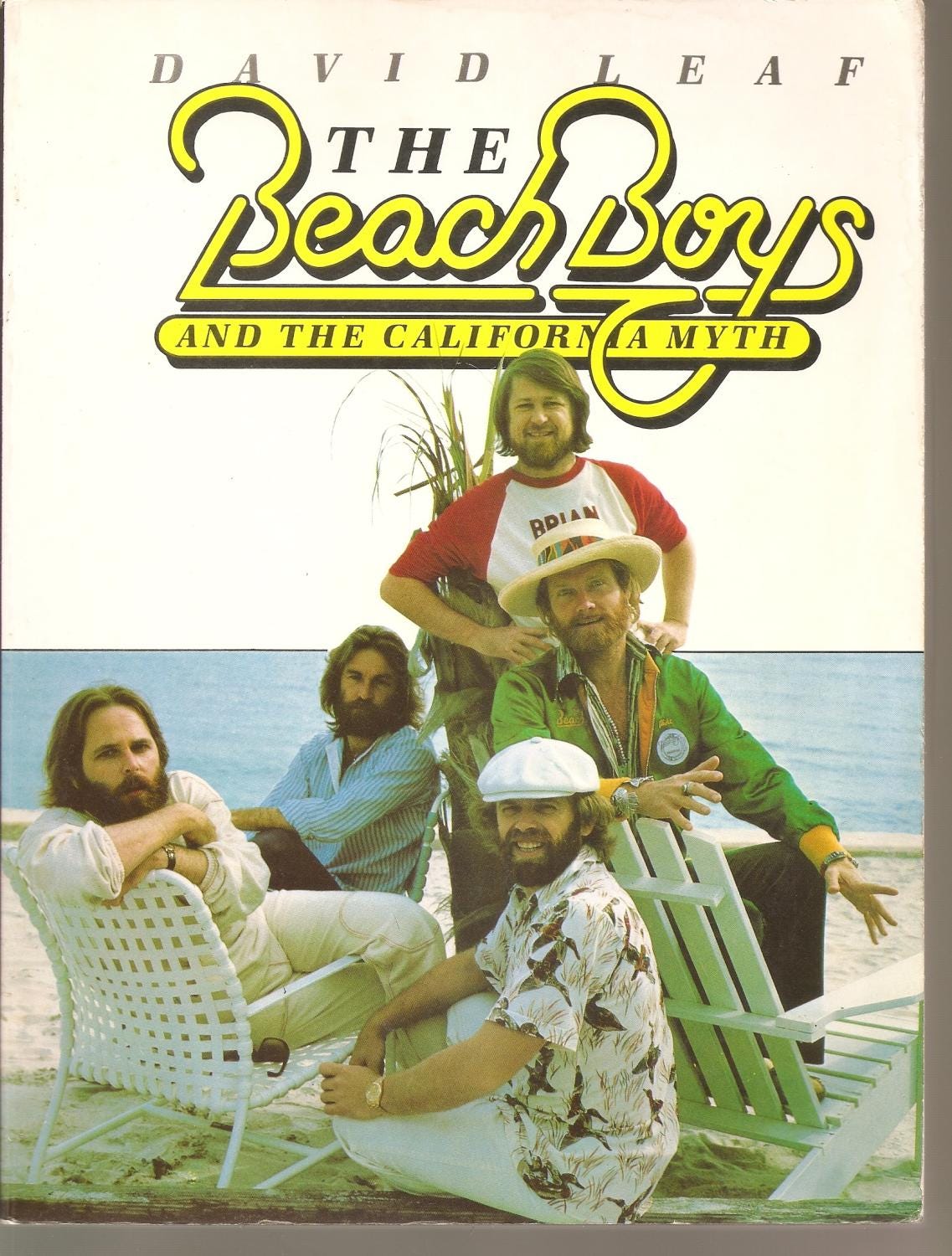

The book was The Beach Boys and the California Myth by David Leaf. David, who would become a very close friend and confidant of Brian and his family through the years, an usher at Brian and Melinda’s wedding and godfather to their daughter Daria, wrote the first extensive history of the band. It was the first exploration of Brian and the difficulties, both mental and external, that he encountered. It was the first detailed look at Pet Sounds and its creation, and the mythical and ultimately aborted (for nearly four decades, anyway) Smile project.

In short, David set much of the narrative of Brian’s and the band’s stories from that point, and he, more than anyone, was instrumental in promoting what had been a commercial flop upon release in the fall of ’66 into what many consider the greatest album ever recorded.

Including a troubled, oft-depressed 18-year-old from Connecticut.

But first, a little long detour – sorta like taking the meandering, maddeningly curvy PCH from Hearst Castle to Big Sur instead of the straight shot on the 101 …

*****

I thought I had already been a big fan – an achievement, considering I couldn’t stand them at first.

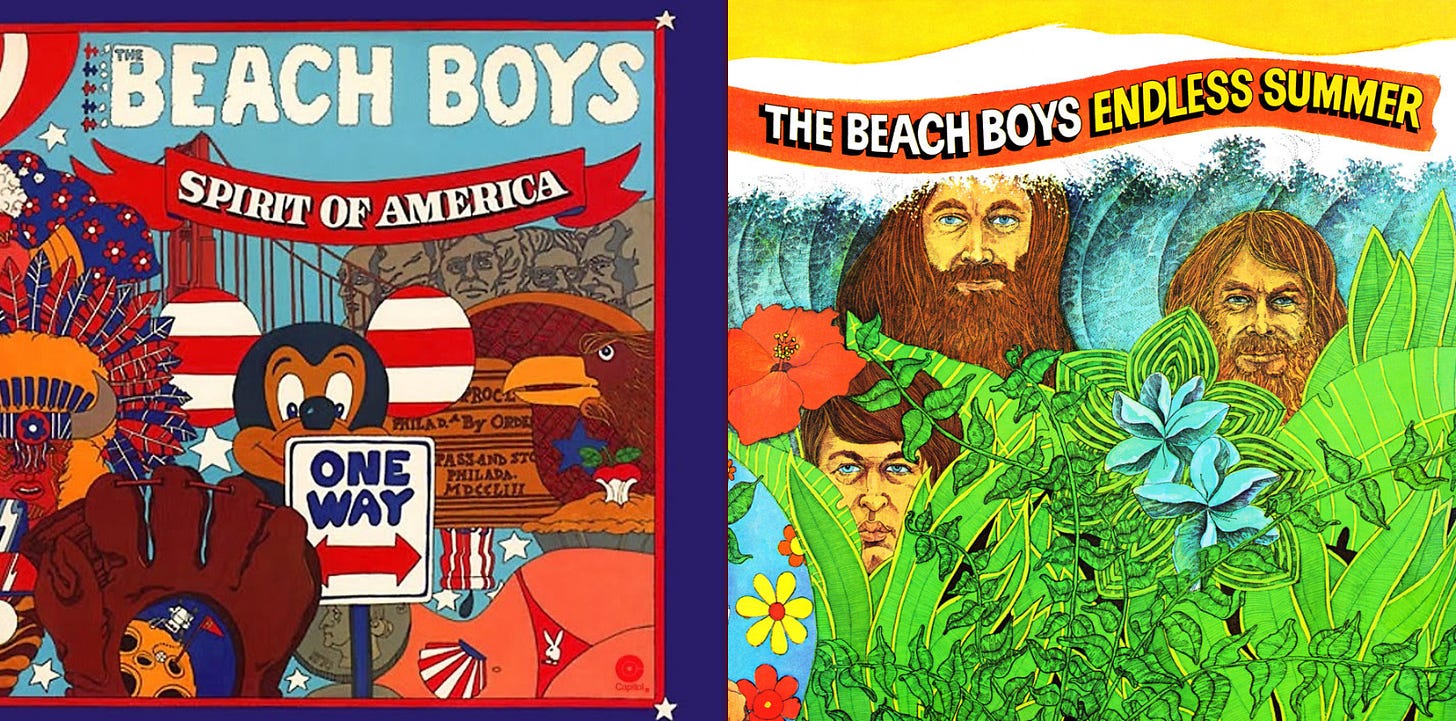

I first became aware of them in 1974, ’75, during the group’s resurgence. Capitol took advantage of the American Graffiti-inspired nostalgia wave to repackage many of their early hits into a two-LP anthology. Endless Summer sold millions of copies, reached number one on the chart, and laid the perfect defibrillator shock to the chest of the group’s dying career.

Also, I was starting to hear them in regular play in my early days of listening to the still-freeform FM stations; the songs struck the right chords of remembrance with an audience that grew up with them on AM, and then went through the disillusionment that came with Vietnam, riots, assassinations, and Nixon (who resigned weeks after Endless Summer’s release). Just as the nostalgia wave sent a new jolt of energy to the early rock’n’rollers and doo-woppers of the ’50s, the same thing was happening with the ’60s kids as they approached or crossed 30, thanks to The Beach Boys. The songs of surf and sun and cars and girls brought a lot of listeners back to a happier time. (And while the four ex-Beatles were going strong with their solo careers, only fairly recently disbanded, Capitol had already begun the anthology process with them, too – the red 1962-1966 and blue 1967-1970 double-LP sets.)

They were all over the radio. And I just didn’t like them. I couldn’t stand having them shoved down our throats by the radio. I began really paying attention to music, the summer of ’71, between fourth and fifth grades, and the male voices I heard in the ensuing years (the young Donny Osmond and Michael Jackson aside, of course) were kinda manly and/or usually loud – think James Brown, Marvin Gaye, The Who, Rod Stewart, Deep Purple, the Stones, Grand Funk, Bad Company, Barry White, Chicago. The Beach Boys, on the other hand, had these soaring falsetto harmonies that sounded, well, girly. Femme. (Strange, I know, especially if you know me, considering I would transition 35 years later.)

Then there was the late night in the summer of 1975 that changed everything. Our house didn’t have AC, and it was warm and sticky, even with the windows open. That spring, my father, after years of finding the time and money to do it himself (well, with a little help from me as often as not), had finally finished transforming our cellar from a damp cinderblock space into a den, complete with new orange indoor/outdoor carpeting. It wasn’t the most comfortable place to sleep, but it was cooler, drier, and it had the added bonus of letting me play my radio late at night without bothering anyone.

As I laid there this particular overnight, I suddenly perked up to the sound of a car revving and peeling down a street …

“She’s real fine, my 409! She’s real fine, my 409! My fourrrrrr, ohhhhhh, niiiiiine!”

The harmonies! Those are The Beach Boys? Whoa!

I was big into cars, whether it be watching races on those occasions when ABC’s Wide World of Sports showed them, or racing Hot Wheels and Johnny Lightnings, or building models of McLaren Can-Am cars and various dragsters. And The Beach Boys were into drag racing? Cool!

From that point, I looked upon The Beach Boys with a more open ear. (And in time, I came around on The 4 Seasons as well, as Frankie Valli was starting to fly solo close to full-time.) By that fall, I was hooked. Between my allowance money and Mom ordering from the RCA Record Club, I began buying albums on cassette, in addition to taping songs off the radio. My first album was the ensuing Beach Boys anthology, Spirit of America, then Endless Summer. Spirit of America had “409,” and it also had a lot of songs that went beyond the big hits: “Don’t Back Down,” “Break Away,” “Do You Wanna Dance,” “The Little Girl I Once Knew,” “This Car of Mine,” “Please Let Me Wonder.” I was taken. I bought 15 Big Ones, the “comeback” album, when it came out the next year.

It was no surprise that The Beach Boys would be my first arena concert, at the New Haven Coliseum – June 18, 1978, between junior and senior years of high school, with Charles Lloyd opening. Thirteen months later, fresh out of high school, I was among the 40,000 or so toughing out the brutal sun 7/14/79 at the Yale Bowl to see them headline, with The Cars, Eddie Money, and The Henry Paul Band on the undercard, and Flo & Eddie emceeing. (“It’s hot as shit!” was as clever as they got.)

*****

Brian invented California for many of us. By that, I mean he created a word and sound image that even the most jargon-bound, snappy-phrasing marketing geniuses couldn’t imagine conjuring and could never buy. The Beach Boys’ songs were what people across the rest of the country – and around the world, for that matter – thought of when they thought of California. They didn’t think of San Francisco, or the forests of NorCal, or the San Joaquin Valley (where I spent eight years, in Fresno), or the Inland Empire. They thought of the SoCal coast – Santa Barbara and Ventura down to San Diego, with L.A. as the epicenter.

The girls on the beach – California girls, with suntans and French bikinis. Boys jacked up for the Friday-night football game – Brian tapped into that frame of mind, having been a quarterback and center fielder at Hawthorne High. Car culture galore, in ground zero of car culture, of hot rods and custom machines, thanks to Brian’s collaborations with a DJ and racing enthusiast named Roger Christian. The ’61 Impala with the 409-cubic inch engine. The ’32 Ford – the little deuce coupe. The street race between a fuel-injected ’63 Sting Ray (the most desirable Vettes, the one year with the split rear windows) and a 413-cubic inch Max Wedge super-stock Dodge Dart. The racer who shot his mouth off and now regrets it as he prepares to drag, and the girlfriend reassuring him everything would be alright. From Dennis came the scenario of restless guys getting around on Friday nights, looking for new places to cruise.

And yeah, surfing. A sport invented in Polynesia 1,500 years before, which made its way to Hawai’i in the ensuing centuries, then to California in 1912, introduced there (and eventually Australia and New Zealand) by Duke Kahanamoku. But Brian and his musical family took surfing from a mostly regional sport here to the rest of the country and, again, the rest of the world.

When they began recording in 1961, they needed a gimmick that differentiated them from other groups. So the story went, cousin Mike Love provided their original name, the Pendletones, after the brand of plaid shirt then popular with surfers, while brother Dennis, the lone surfer in the group, provided the cred and the springboard to writing surfing songs. Surf music was already popular, thanks to Dick Dale and The Belairs, among others, but only as instrumentals. Vocals – especially these five-part harmonies – were new. The name change to The Beach Boys, though, wasn’t their idea – Russ Morgan, the promo man at Candix Records, which released “Surfin’”/”Luau” just past Thanksgiving 1961, changed it without them knowing until the record actually came out.

Actually, that might have been a wise choice. Pendletons were a fad that faded (though they didn’t go away totally – the shirt manufacturer reintroduced the surfer shirts popularized by the group for the company’s 80th anniversary, and they’re still being made). But the beach? That’s forever. That’s eternal – as sure as the tide rushes in and laps on the sand and flows out, as sure as the waves crash and churn against the coast, a mix of calm ambient sound and powerful violence all at once.

*****

Okay, detour over – back to 1980.

The more I read Scott’s copy of David’s book, the more that I was filled with sadness and wonder and a sense of mystery.

The sadness, of course, was Brian’s troubles – the mental and alleged physical abuse by his father, Murry; the constant pressure from his record label to feed the beast and provide more product; the pressure to prove himself at a time when musicians often didn’t write their own songs and certainly didn’t produce; his nervous breakdown; the evolution of his writing and composing away from fun and sun and surf toward introspection; the lessons he learned from Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, using the same core/corps (either word fits) of studio musicians; the self-inflicted competition with The Beatles; the drug use and the eventual shelving of Smile and retreat to the sandbox and the bedroom.

Also, for all the wildly popular songs he wrote about the surf and sun and fun, Brian was an outsider. (I get it – I have friends all over the place but feel like I belong to everyone yet no-one at the same time. That sense of not belonging anywhere. Kind of an isolation amidst the occasional socializing.) In a lot of the band’s photos from the early days, he looks kinda detached, kinda sad, depending on your view. He had some cool cars, but he famously didn’t surf – not until that NBC special in 1976, where Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi, dressed as cops, forced Brian out of the house and to the beach to surf.

Also, he loved ’50s Black-based R&B and rock’n’roll (most famously borrowing Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen” for “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” and “Gee” by The Crows as part of the opening medley of Smile), but most of his harmonies came straight out of the taffeta-era white vocal groups: The Four Freshmen and The Hi-Los. And he wrote “Don’t Worry Baby” as an answer to his all-time favorite song, “Be My Baby,” in the hopes that Ronnie Spector would record it. (That wasn’t gonna happen with the domineering Phil Spector in charge; he hated Brian, probably because he was competition. Ronnie would eventually sing it to him decades later.) Like the Gemini he was, he was a study in contrasts.

Then came Pet Sounds, as mentioned.

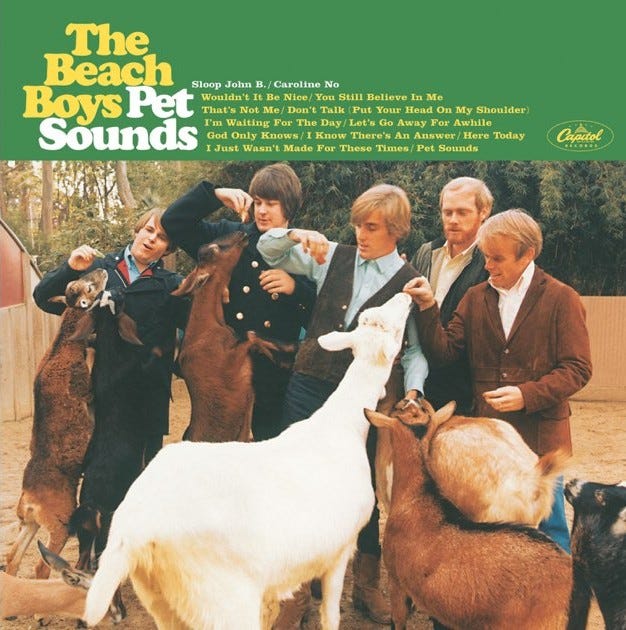

In the midst of reading the book, I went down to the student center, Hillwood Commons, one Sunday midday to see if they had a cassette of the album. Sure enough, it was a double-album tape: Pet Sounds on one side, Carl & the Passsions – So Tough on the other. (Warner Bros. packaged the two like that on LP as well.) So I ripped off the wrapping, popped it into the cassette player …

The first song: “Wouldn’t It Be Nice.” Cool, but I’d heard it so many times. Hurry up and get to the rest of it!

Next up: “You Still Believe in Me.” The haunting high whoooo and piano note at the beginning … the finger cymbal and a keyboard and a tympani and a bicycle bell. And the harmonies! All brought home by the two honks of a bulb bicycle horn. Oh. My. God. I began to choke up right from the get-go. I wanted to cry, too.

“That’s Not Me,” a hymn for the non-secular. A song about growing and evolving and the pain and increasing solitude, which wasn’t so pretty. “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder),” another beautiful composition, which starts like a hymn and asks for his girl to be quiet and just absorb the bliss of the moment. The tympani and organ that announce the upbeat and hopeful “I’m Waiting for the Day” when you can love again. The lavish, tropical instrumental “Let’s Go Away for Awhile,” which sounded like it belonged in an airline/travel commercial. (In fact, I did use it as the musical bed for an airline commercial I made for my TV class my junior year.)

“Sloop John B,” a great tune, but again, I’d heard it many times already, and it didn’t fit with the rest of the album. (I did learn from the book, though, that Capitol had it inserted because the suits demanded a hit. Never mind that at least three other songs on the album would become hits, Beach Boys classics.) “God Only Knows.” Another one I’d heard plenty of already, but it was so damned beautiful (and I use that adjective a lot with this album, though with good reason), one of his finest compositions. And it fit perfectly within the fabric of the rest of the album. “I Know There’s an Answer” – a louder and higher-energy piece about the soul-searching that we sensitive (and overthinking?) people do in trying to find the meaning in our lives. (I still don’t know what my purpose is or has been; maybe it’s for others to decide.) “Here Today” – my least-favorite song here. Just a little too simplistically sing-songy for my liking. But oh, God! “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times.” The melancholy, despair of looking for a place to fit in and not getting any help in the process. Then the storm – the turbulence of sadness and some anger among the isolation. It became one of the themes of my life for so many years. (These days, I feel I’m just about right for my times – I’m where and when I’m supposed to be. I just wish I got there decades ago.) “Pet Sounds,” the instrumental – a trip through the tropics, a burst of sunshine amidst the clouds. And, of course, the wistful sadness of “Caroline, No” to close it out – that dog barking and the train whistling as it heads away.

The intricacies of the compositions. The layering of so many sounds. The beauty. The emotions. They came from the heart of a troubled soul and they spoke loudly at that moment to this troubled soul. In time, I would learn about the brilliant team of studio musicians who laid down everything but the vocals. I would eventually plunge into the assorted jumble of sounds, the jigsaw pieces and scraps of fabric from which Brian wove these masterpieces, found on the Good Vibrations box set, as well as the box sets of the Pet Sounds and Smile sessions. But this initial listen to the album as a novice music fan left me stunned, emotionally drained. Exhausted. I’d never heard anything like that before, and never would since, 45 years since it first reached my ears. The best music, regardless of genre, hits the listener viscerally, strikes a personal chord. Pet Sounds impacted me, spoke to me, resonated with me, at a level much deeper than any other recording, and at a precarious time in my life.

Thanks to David’s book (updated and re-published in 2022 as God Only Knows: The Story of Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys and the California Myth), I was also able to learn how the two Beach Boys albums released the year prior, The Beach Boys Today! and Summer Days Summer Nights – recorded after he retired to the studio, post-breakdown – were a harbinger of what we would hear a year later, both in sound and in subject matter. And I also learned about the aborted Smile project and how “Good Vibrations,” Brian’s artistic pinnacle, which was to have been the crowning piece of the album, fit into the scheme of things.

I think it was Casey Kasem on American Top 40 when I was in high school who told the story of how “Good Vibrations” took six months to finish and cost what was the then-staggering $40,000 to make. I’m guessing the tale was tied into Todd Rundgren’s note-for-note 1976 re-creation, which reached the 30s on the chart. That would make sense, as Todd went on to produce (with much well-documented acrimony with Andy Partridge) what I considered the Pet Sounds of the ’80s: XTC’s Skylarking – a 1986 song cycle about a relationship from initial courtship to death do us part, also interrupted by a song the label dropped in (in this case, “Dear God” replaced the beautiful “Mermaid Smiled” after Geffen’s initial pressing) for want of a hit single. There have been so many musicians since who have referenced Brian and this fertile 1966-67 era. The title of one of my favorite albums of the ’90s, by the Providence trio Velvet Crush, came from Brian’s description of Smile at the time: Teenage Symphonies to God. (It also has one of the best album covers I’ve ever seen: an homage to the clever/cartoonish artistic ‘60s Columbia Records style.)

I would also learn about “Surf’s Up,” the title song to one of the several ensuing albums that recycled parts of Smile, and its origin – Brian’s sweet piano and angelic high notes wed to Van Dyke Parks’ abstract lyrics. It’s one of the most beautiful songs he ever composed, right up there with “God Only Knows” among my favorites of his. And in the years to come, Paul McCartney (whose favorite Beach Boys song is “God Only Knows”) has said a great many times that Pet Sounds was the album that spurred The Beatles to record Sgt. Pepper. Their masterpiece came out in June 1967 and took the entire world by storm in only the way The Beatles could. But as for The Beach Boys, Pet Sounds languished, they pulled out of the Monterey Pop Festival – which took place the week before Sgt. Pepper’s release, with Jimi Hendrix telling the audience, as he did on his first album, “You’ll never hear surf music again” – and the group almost suddenly seemed irrelevant.

As for Smile, it would remain a deep mystery, the great what-could’ve-been, and many bootlegs of various bits and pieces (and sound qualities) would appear over the ensuing years.

*****

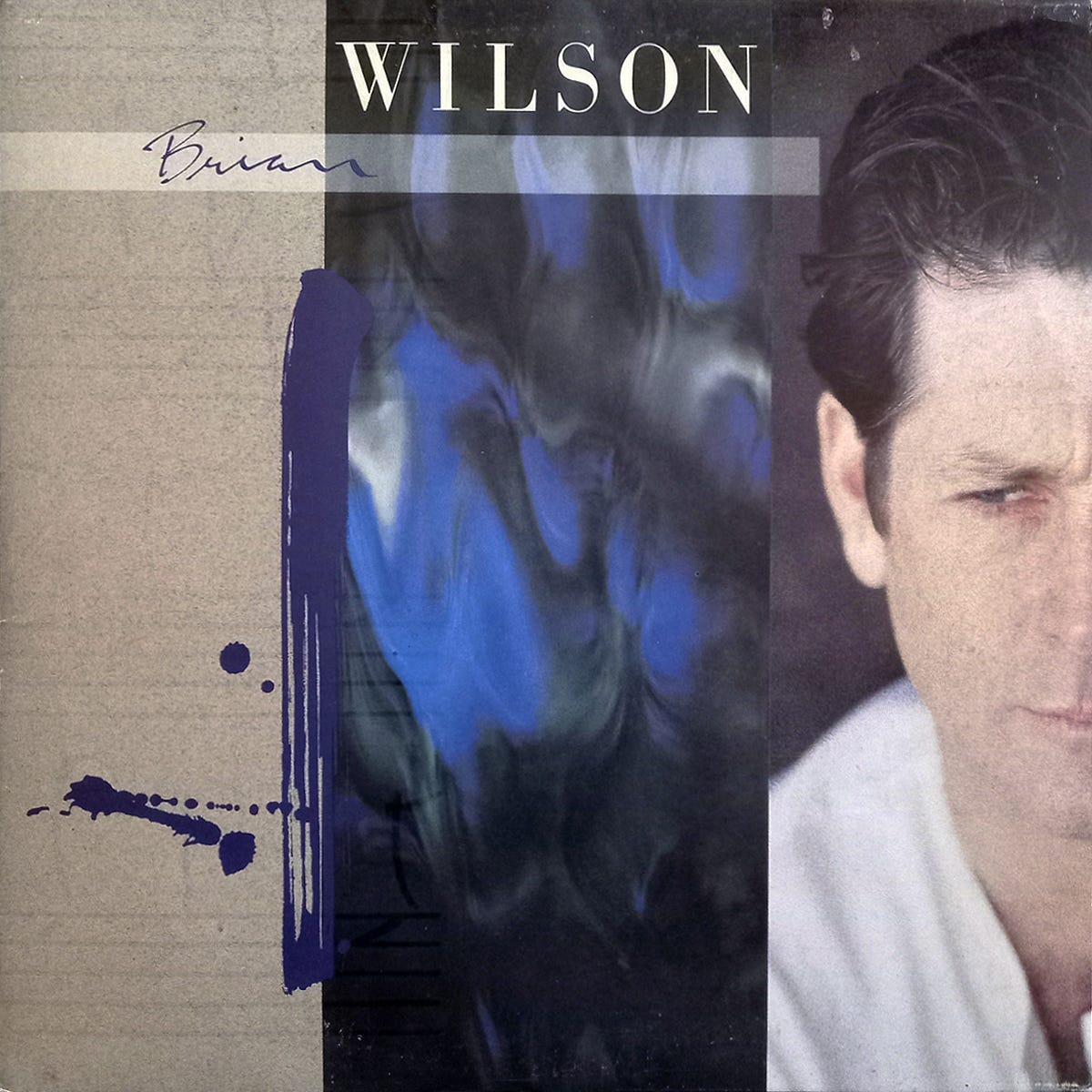

July 1988. I was working as a sportswriter at my first paper – my hometown-of-sorts paper, the Waterbury Republican-American – but also was freelancing album reviews and, eventually, a music column, starting in 1984. The promo copy of Brian’s at-long-last solo album arrived – the record, plus the press kit in a small blue vinyl three-ring binder, the type a student would use back then.

The Beach Boys had gone through hell, much of it self-induced, in the years following Pet Sounds. The first time I saw them was at the New Haven Coliseum in June 1978 (Charles Lloyd opening), and then again a year later, July ’79, with over 40,000 of my close personal friends on a brutally sunny Saturday at the Yale Bowl (with The Cars, Eddie Money and The Henry Paul Band, with Flo & Eddie as MCs). I didn’t realize that I was seeing them at their most fractured and downright acrimonious and volatile and often drug-induced period, producing some of the worst albums they ever made.

They eventually became almost an afterthought to me, between the new sounds into which I plunged – I went to school a half-hour from Manhattan from 1979-83, the last great fertile period of music, with punk starting to morphing into hardcore and new wave and alternative dance music and primordial Goth, the ground floor of hip-hop, the influence of reggae, and plenty of experimental and oddball sounds as well – and Dennis Wilson drowning at the end of 1983.

I was pleasantly surprised but apprehensive when I first put on the first, self-titled, album by Brian under his own name, produced by Brian, Andy Paley, Russ Titelman … and Brian’s so-called “therapist,” Eugene Landy, who kept interfering with the process. Any worries I had about the album immediately fell away with the opening of the first song, “Love and Mercy,” which would become his theme – the final song of his encores – until the very end. Yep, this was a Brian production, alright, or at least Brian-style – a bit of wide-eyed adult innocence in the lyrics, a blend of many sounds beneath, also with some whimsy enough hooks to keep you interested. That, a brief and beautiful piece of classic Beach Boys-style a cappella harmony called “One for the Boys,” and an 8-minute epic (the brainchild of Warner Bros.’ then-president, Lenny Waronker) called “Rio Grande” to close out the album. It was in the spirit of the original 12-minute version of “Heroes and Villains” – watered down for the watered-down Smiley Smile album. If anything, it proved that Brian still had it in there somewhere.

I couched the longish review I wrote for the Sunday paper in terms of healing. There was the rousing speech Jesse Jackson had just given the week before at the Democratic convention; a nice phone call I had with an ex-girlfriend (and former newspaper co-worker), Ann Marie; and Brian’s return.

A few nights later, I was answering phones on the Sports desk, taking down local game and golf results, when I got a phone call asking for me.

“Hi, Fran. This is David Leaf calling from Los Angeles.”

He had gotten hold of the review and wanted to talk about the album. The crazy thing was that it was so damned loud in Sports that I thought he said he was David Lee. I thought he was just a fan who found out about it somehow, pre-Web, and it wasn’t until a few minutes later that I realized “Holy shit! You idiot – it’s David Leaf!” The details of the call are lost to the ether, but it was a great conversation before I had to go back to taking scores.

Life isn’t fair, though. The album got excellent reviews, but it wasn’t a big seller. Meanwhile, The Beach Boys, with the increasingly unpopular (and, in some circles, ridiculed) Mike Love at the helm, recorded a song for the soundtrack of the Tom Cruise film Cocktail, which was released around the same time; “Kokomo” went to No. 1 on the chart. (Congratulations, Mike – you led one song that reached the top 40 and topped it. Brian was the driving force of 34 of the group’s top-40 hits, three of which reached the top.)

*****

May 1999/July 2001.

Many things had transpired in the interim. Brian had recorded a follow-up album, Sweet Insanity, which was essentially a Landy album (and I’m glad to say I never listened to it; never wanted to). Landy was pretty much holding him captive at that point, and it took the efforts of Melinda Ledbetter (who eventually became the second Mrs. Wilson), brother Carl Wilson and David to finally spring Brian away from him.

Brian had begun the healing process with his two daughters from his first marriage, Carnie and Wendy, who had gone on to form Wilson Phillips (with Chynna Phillips, daughter of Mama Michelle and Papa John) and have some chart success. Brian appeared on bassist Rob Wasserman’s 1994 album Trios, recording “Fantasy Is Reality/Bells of Madness” with Rob and Carnie. Also in 1994, Don Was released his excellent Brian documentary, I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, which included a couple of songs with the daughters. Post-Wilson Phillips, they regrouped for a short time as The Wilsons, and Brian appeared on two songs on their self-titled 1997 album. Carl died of cancer in 1998, leaving Brian as the Lone Wilson Standing. Also around that time, he and Melinda – who eventually adopted four children – moved for a few years to, of all places, St. Charles, Illinois, where he had a basement studio built and collaborated with songwriter/producer Joe Thomas to record his second official album, Imagination.

Personally, I escaped a union-busting at the Republican-American at the end of August 1992 to become the entertainment editor/music writer at the New Haven Register, in the city where I lived, and where, after graduation, I became a part of the alt-music scene. Moving to the Register, the state’s second-largest paper, I was offered a lot more interviews with artists to preview shows, either in features or my weekly music column, and was able to line up more interviews that I wanted.

And in the spring of 1999 – surprise, surprise, surprise! – Brian was embarking on a tour for the first time since the late ’70s, his first with his own band. And he would be coming to Mohegan Sun on June 20th, his 57th birthday. And I never asked him, but I had a sneaking suspicion David had something to do with me being offered an interview with Brian.

Of course I said yes, but it scared the hell out of me initially. I mean, this was someone whose music meant that much to me. Yet, I had to be thoroughly professional and not come off like a gushing fanboy. (This was a decade before my transition.) His story was gettin’ real well-known at that point, so I had to ask questions that hadn’t been asked yet, best I knew (and keep in mind that the Web as we know it was in its primordial phase, so it’s not as if I could research online). I also had to ask questions that I felt would keep the reader interested – and, most importantly, questions that would keep Brian engaged long enough to keep his interest and give me some excellent answers.

So there I was, Friday night of Memorial weekend, 9 o’clock, sitting in the kitchen of my apartment, talking to Brian Wilson – something I never could have imagined as that college freshman listening to Pet Sounds for the first time. Most of my interviews at the Register were phoners, out of necessity, and all but a few took place in the office, not at home on my days off. (Well, there was that Friday three years later where I had back-to-back phoners at home with Tony Shalhoub and Luciano Pavarotti – and no, I can’t possibly make this up.) But it was quieter and more relaxed, and that was a help with calming my nerves.

Ther day after Brian’s passing (and not knowing this piece would be a magazine-length post), I put up a Substack that contained that interview. It actually turned out much better than I expected, and not just because I didn’t know what to expect. We covered a broad range of subjects in the half-hour before he finally said, “I can’t talk anymore.” In my 11 ½ years at the Register, I only kept two interviews in Q&A form; one was Ray Charles, in 1993, and the other was Brian. One of the things I asked him about was his overcoming his well-known stage fright.

“My wife and my collaborator, Joe Thomas, got together with me, he related.” They said, ‘I think it’s time you go out and did a tour. It’s been 10 years since you’ve done anything as an artist. Let’s go out and we’ll promote a tour.’ I said, ‘No. I wouldn’t draw anything [attendance-wise].’ They said, ‘You wanna make a bet? You wanna make a fuckin’ bet?’ They said, ‘We’ll schedule four shows in March.’ I said, ‘I’m gonna get booed.’ I went on tour and people gave me standing ovations.”

Brian, who didn’t know how to not be honest, sincerely thought he would be ridiculed. Instead, he tapped into a gusher of love and affection around the country – and eventually, across the ocean, in England – for an artist who not only provided much of the soundtrack of fans’ lives, but overcame a hell of a lot to get back to this point.

I saw that at Mohegan Sun. And prior to the show, I met finally David in the flesh. And following soundcheck, he introduced me to Brian. It was only about 10 seconds; we shook hands.

“Hi, Brian.”

“Pleased to meet you.”

“Happy birthday!”

“Thank you very much.”

That was it. But still …

Anyway, it was obvious that he was quite nervous onstage. But it was also quite obvious that he was in good hands. Melinda was there. And the band more than had his back. The core of his band came from the members of the Wondermints, an ace L.A. pop band heavily influenced by Brian: Darian Sahanaja, Nicky Walusko, Probyn Gregory and Mike D’Amico. The night he met them, at a show in the mid-’90s, Brian told the legendary L.A. DJ Rodney Bingenheimer, “If I’d had those guys in 1966, I could have toured Smile.”

That would be years in the future. For the moment, the band put his mind at ease; they knew his sound, they fell into place behind him quite easily, and it would be one of many enjoyable shows to come. They played 24 songs, starting with “California Girls” and ending with “Love and Mercy.”

*****

In June 2000, I was able to interview Brian again for the Register, and he seemed more relaxed than the first interview. It was a pleasant interview, but the concert was much more memorable – the greatest concert I’ll ever see.

It was early in the Pet Sounds Symphonic Tour, where one of the sets would be a front-to-back playing of the album, backed by an orchestra. Brian and his band returned to Mohegan Sun – but this time, in a considerably larger space, a circus tent that served as a temporary venue as the Mohegan Sun Area was being completed. My then-girlfriend, Shannon, and I took our seventh-row aisle seats, and I just couldn’t wait. The emotion I felt this time around was not apprehension, but anticipation.

Brian and the band came out and did two sets of his contemporary songs peppered among the Beach Boys tunes, both hits and lesser-known selections. The second set began with Brian Wilson playing “Brian Wilson,” as in the intro to Barenaked Ladies’ homage to him. Then, after a break, they returned, accompanied by a 54-piece orchestra onstage and a great deal of anticipation in the audience.

My God, my God. I just can’t tell you how special it was, can’t do it justice with words. Pet Sounds, of course, was a studio project, intricately pieced together but never played with all the instrumentation in one place. Paul Mertens arranged the live set, and if anything, they came as close as humanly possible to capturing the sounds that swirled around his head in 1966. It was another emotional moment … and when they were done, they and the orchestra gave us “Good Vibrations” as the cherry on top.

I was ready to leave, but nope! There would be a fourth, encore, set. Brian came out in a striped shirt, strapped on a white Fender bass with a flame job, and played a half-dozen Beach Boys hits from the first chapter of their career. In a way, it was a screw-you to Mike Love, under whom The Beach Boys (he owned the name) became a sheer nostalgia, “Fun, Fun, Fun”-plus-“Kokomo” act. I was not expecting this. Just another dimension added to what was already an evening for the ages.

At this point, I thought that now I’ve really seen something I never would’ve imagined. And again, Brian owed us nothing. From this point, anything he gave us was gravy.

I saw Brian and the band play the album twice after that. Two months after that concert, I brought my brother Jim to the nearby Oakdale Theatre. The show was shorter, just the band without the orchestra, but it was still a marvel to behold. I moved to Fresno in 2004 and saw what was planned to be his final performance of the album, in January 2007 at the Paramount in Oakland. (Spoiler alert: It wasn’t.) The pleasant surprises at that show were Al Jardine accompanying Brian on several songs, with Ricky Fataar backing Al’s lead vocals on “Help Me, Rhonda” in the encore. (Ricky and fellow South African Blondie Chaplin were Beach Boys for two albums in the early ’70s. In between that and his long career of drumming for Bonnie Raitt, he was Stig O’Hara, the George Harrison character, in The Rutles. Blondie became, among other things, a longtime backing singer and musician for the Stones.)

Again, everything from the first time I saw him was gravy, and there was plenty of gravy. And, five years later, then some.

*****

Backtrack to September 2004. Or, should I say, March 2005.

Now that Brian had successfully conquered Pet Sounds live, would he revisit Smile in the studio and finally finish what he started?

It was David Leaf’s late wife, Eva, who spurred Brian into doing it. At a 2000 Christmas party, he sat next to her at the piano and asked her what she wanted for Christmas, and she said she wanted to hear him play “Heroes and Villains.” (The song, as originally intended for the album, was 12 minutes long in its original form, but trimmed to 3 minutes and change so Capitol Records could release it as a single.) Smile had long been a tiptoe-around subject among Brian’s inner circle, and he had shut down every query about whether he would ever consider finishing it – which he finally did in 2004, with his own band. When she told him what she wanted, the room went quiet. (All I could think of was Tom Waits doing Red Sovine’s “Big Joe and Phantom 309”: What’s the matter? Did I say something wronnng?) But instead of reacting negatively, Brian actually pondered finishing it. Somehow, she managed to break through.

So the news came out that Brian and his band would be working on the final piece of his career puzzle. But which version would we hear? After all, a world of things had transpired between the 26-year-old Brian and the 62-year-old Brian. How different would his 2004 vision be from 1966-67? And, as the huge number of bootleg versions through the years bore out, there were just so many shards of sounds to include or discard.

Anyway, I was so afraid of how I would react to the album that I didn’t buy it for six months. Finally, there was just that one night at Target when I saw it on the rack and said “screw it” and finally broke down and bought it and braced myself.

It started with the medley of “Our Prayer”/”Gee” and ended with “Good Vibrations.” “Heroes and Villains” was stretched, with its “in the cantina” verse, to about five minutes, “Good Vibrations” was slightly expanded to include alternate lyrics, a few bars of additional vocal harmony in the bridge, and “Cool Cool Water” was replaced with “In Blue Hawaii.” So maybe we wouldn’t hear the original ’60s vision. But what we heard was lovingly done, with the help of his amazing band, and it more than held his own.

And seven years later, in November 2011, we got the full treatment at last when Capitol released the lavish The Smile Sessions box set. Again, no disappointments. And clearly, this Beach Boys version was influenced by Brian’s 2004 version, with the longer “Heroes and Villains” and “Good Vibrations” included. Did it hit with the impact of Pet Sounds? No, not quite. We had heard so many of these songs over the decades that there wasn’t that visceral hit to the consciousness that Pet Sounds possessed. But it was beautiful, and it was great to hear, at long last, a finished piece by the man who envisioned it in the first place.

The odd thing about Brian’s Smile was that he received a Grammy for best rock instrumental – for “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow,” the very fire-element piece that so freaked him out back in the ’60s. Go figure …

*****

June 1, 2012.

It was the Friday three days before my birthday. And one of my closest friends, Joe, had sent me a chunk of money a couple weeks before to put toward a seat at The Beach Boys’ 50th Anniversary tour stop at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley.

I can’t tell you how much I appreciated it. I had been out of work 2 ½ solid years when The Fresno Bee – the paper for which I moved from Connecticut in 2004 and which laid me off in 2009 – brought me back part time on the copy desk, in September 2011. I had pretty steady hours through Christmas, but afterward, they dried up, so I was struggling some, on top of being in a difficult living situation. And this was just incredible. The Beach Boys had been my first concert, in 1978, and I would get to see them what I knew would be one final time, as all the surviving members – Brian, Mike, Al, Bruce Johnston and Dave Marks – would play in a band blended from Brian’s and Mike’s lineups.

I chipped in some money, too, and wound up with third row center. One final magical moment – and under the stars. They played 46 songs in all– two full sets and an encore. They touched every era of their career, from “Surfin’ Safari” and “Surfer Girl” to “That’s Why God Made the Radio,” the title song to their new album, and so much in between, both hits and roads less trod. Some lead vocals from Brian, Al and Mike – they played “Kokomo” to start the encore, and it was weird to see Brian up there performing it – and some originally sung by Brian’s brothers.

By the time I had to rush back to the BART to catch one of the last trains back to my car in Pleasanton, I was just plain drained from the euphoria. In fact, I was so exhausted that I couldn’t get myself out the door the next morning to go to Fresno’s Pride Parade, always the first Saturday of June, and always a huge date for me and for the whole Tower District social calendar. It was just unseemly for me, who was treated so lovingly by my friends when I came out three or four years before, to miss this, but the body was saying “No mas.”

If I knew what was coming, though, I might have thought differently. At month’s end, I was told that my measly part-time job at the Bee was being cut. So come mid-August, I was in the cab of a 26-foot Penske truck, with my beater Camry on the back, driving 3,000 miles across the country and moving home to Connecticut.

And at the end of September, Mike Love announced he had booked some more 50th Anniversary Tour dates – only without Brian, Al and Dave, and without telling them. He denied “firing” them, but just because one doesn’t say “firing” doesn’t mean they weren’t fired. Yes, he fired Brian Wison from The Beach Boys. So Mike and Bruce would carry on with the Mike Love Kokomo Revue (I refuse to call them anything but), while Al would join Brian on tour – in time, his son Matt would come aboard to sing the high notes – and Dave eventually rejoined Mike’s group. It should never have come to this.

*****

There were some great documentaries about Brian: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, and, in 2021, Brent Wilson’s (no relation) Long Promised Road, where Brian and Rolling Stone editor Jason Fine drove around L.A. and suburbs to various places and landmarks from his past.

But biopics? Ouch! My head still reels when I think of that ABC movie Summer Dreams: The Story of the Beach Boys back in 1990, where just everything felt wrong – right down to the beards that I think were left over from the stoning scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian. There was also Grace of My Heart in 1996, starring Illeana Douglas as a singer/songwriter very loosely based on Carole King, with Matt Dillon playing an extremely loosely based Brian-like figure (and romantic interest) with a tragic ending.

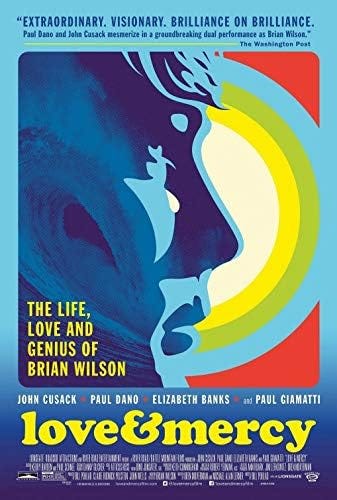

But then came Love and Mercy, directed by Bill Pohlad, in 2014. I waited a month or so, again out of apprehension, but went to a matinee with my friend Joe.

So much of Brian’s story had been so well-known by this time, and there were so many more casual fans attuned to it as well as the hardcore fans, that it was a matter of “he damn well better get this right time.” Well, Pohlad did. Having two actors star as Brian was a stroke of genius. It was harder to discern what was real and what was artistic license in the story of the middle-aged, 1980s Brian (as played by huge music fan John Cusack), but he portrayed Brian with what seemed to be the right amount of vulnerability and damage. Paul Dano as the young Brian, however, was above and beyond. He was a ringer for ’60s Brian and he was absolutely believable, right down to the descent into madness. Pohlad’s direction was also key. The scenes where Brian made Pet Sounds and part of Smile were cut in a way that conveyed the urgency and the fanatical pace with which Brian was working and envisioning. And in the accuracy department, some of the studio players truly looked like their real-life counterparts (I’m thinking of Teresa Cowles as Carol Kaye and Johnny Sneed as Hal Blaine). And the film’s version of the whimsical promo video for “Sloop John B” was especially excellent for replicating all the details and shots of the original. So especially was the scene where Brian performed “Surf’s Up” solo at his piano for Leonard Bernstein’s CBS TV special Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution.

*****

The long decline. Or, it’s so sad to watch a sweet thing die.

Again, everything Brian played after his initial tours with his band was gravy to me. But it didn’t mean that I couldn’t be sad.

I first noticed during the Beach Boys tour that he was moving quite slowly and needed help getting on and off the stage. I had heard something, someone scuttlebutting about a bad back. That would make sense.

When I moved home, there was a stretch of a few years when I was unemployed as often as I was employed, so I couldn’t swing a ticket to see him with Jeff Beck at Oakdale, or playing Smile with his band. Thanks to another close friend, Drew, I went to the Christmas show at Oakdale in 2018, where they performed 1964’s The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album in its entirety, with Blondie Chaplin on backing vocals and a little guitar. But I could see and hear spots where Brian left the vocals to his band and seemed to be distracted.

The last time, though, was truly painful – in September 2019, 10 minutes from my folks’ house, where I was living then, at the Palace Theatre in Waterbury, another show I saw thanks to Drew.

On the positive side, I got to meet some of the band out in front of the theater beforehand: Probyn Gregory (who was, and is, a Facebook friend), Darian Sahanaja and drummer Jim Laspesa, who had once played in a band I was friends with, The Muffs. But then, there was the show itself. It was interesting that the curtain was drawn ahead of time, and Brian was already seated when it opened, as if he’d been wheeled out to the stage. While the band was its usual dynamic, wonderful, caring and protective self, Brian was conspicuous in his present absence. He was there, but he wasn’t. From where I sat, on the floor, it seemed as if he would occasionally chime in a vocal or noodle something on his keyboard, but the focus wouldn’t last long. He seemed to be off on his own planet. Finally, the curtain closed, and I knew it was the last time I would see him.

Then came the pandemic. Then Brian announced his retirement touring in 2023, Melinda died in January 2024, and it was announced late last year that he had been diagnosed with dementia.

But he spent his final days knowing he was loved – by his daughters, his friends, his band, and by a world of people he touched with his gift in so many ways over six decades.

Love and mercy to all who knew and loved him, either personally or through his music.